When you open your browser and type in a website address, your device needs to know where to send that request. That’s where routing tables come in. Think of them as digital road signs that guide packets of data across networks until they reach their destination.

What Is a Routing Table?

Every IP-enabled device — not just routers, but also workstations, servers, and firewalls — maintains a routing table. This table is essentially a list of directions:

- Destination networks (subnets)

- Next hops (where to forward the packet)

- Metrics and preferences to break ties

When multiple routes exist, the device chooses the most specific route. This ensures packets follow the best possible path.

Route Entries Explained

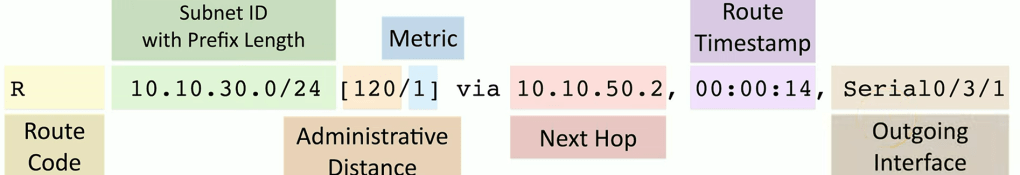

A route entry contains several key fields that help the router make decisions:

- Route Code: Identifies the source of the route (e.g., static, OSPF, EIGRP).

- Subnet ID with Prefix Length: Defines the destination network.

- Administrative Distance: Trustworthiness of the route (lower is better).

- Metric: Cost or preference within the routing protocol.

- Next Hop: The next device packets should be sent to.

- Outgoing Interface: The physical or logical interface used.

- Route Timestamp: How long the route has been in the table.

Prefix Lengths: Why Specificity Matters

Routing decisions favor the longest prefix match. In other words, the most specific subnet wins.

For example, if a device is trying to reach 192.168.1.6, and the table has:

192.168.0.0/16192.168.1.0/24192.168.1.6/32

The /32 (host route) is the most specific and will be chosen.

Administrative Distances: Trusting Routes

Routers often learn about the same network from multiple routing protocols. Since each protocol calculates metrics differently, you can’t directly compare them. That’s why administrative distance (AD) exists.

- Lower AD = more trustworthy.

- Example: Static routes (AD 1) are trusted more than RIP (AD 120).

This ensures routers consistently prioritize the right protocol.

Routing Metrics: Weighing the Best Path

Each routing protocol uses its own metric to determine the “best” path:

- OSPF: Cost based on bandwidth

- EIGRP: Composite metric (bandwidth, delay, reliability, load)

- BGP: Path attributes such as AS-path length

When multiple equal-cost routes exist, metrics help the router decide. Lower values win (e.g., metric 1 beats metric 2).

First Hop Redundancy Protocols (FHRP)

Normally, your computer has a single default gateway — the first router it sends traffic to. But what happens if that router fails?

That’s where FHRPs like HSRP, VRRP, or GLBP come in. They use a virtual IP (VIP) for the default gateway. If one router goes offline, another automatically takes over.

This ensures continuous connectivity and solves a key limitation of IP addressing — one gateway can actually represent many routers.

Subinterfaces: Beyond Physical Ports

Routers and switches don’t just rely on physical interfaces. They can also use subinterfaces:

- A physical port can be split into multiple logical subinterfaces.

- Often used with VLANs on trunk links.

- Each subinterface is configured separately, with its own IP address and policies.

For example:

Ethernet1/1(physical interface)Ethernet1/1.10(VLAN 10 subinterface)Ethernet1/1.20(VLAN 20 subinterface)

This allows one physical interface to handle multiple networks.

Leave a comment